James A. Garfield

| James A. Garfield | |

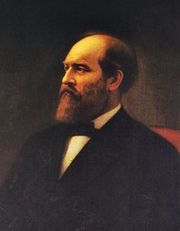

Brady-Handy photograph of Garfield, taken between 1870 and 1880 |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 |

|

| Vice President | Chester A. Arthur |

| Preceded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Succeeded by | Chester A. Arthur |

|

|

|

| In office March 4, 1863 – March 3, 1881 |

|

| Preceded by | Albert G. Riddle |

| Succeeded by | Ezra B. Taylor |

|

|

|

| Born | November 19, 1831 Moreland Hills, Ohio |

| Died | September 19, 1881 (aged 49) Elberon (Long Branch), New Jersey |

| Resting place | Cleveland, Ohio |

| Birth name | James Abram Garfield |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Lucretia Rudolph Garfield |

| Children | Eliza Arbella Garfield Harry Augustus Garfield James Rudolph Garfield Mary Garfield Irvin M. Garfield Abram Garfield Edward Garfield |

| Alma mater | Western Reserve Eclectic Institute Williams College |

| Occupation | Lawyer, Educator, Minister |

| Religion | Church of Christ |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Years of service | 1861–1863 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands | 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry 20th Brigade, 6th Division, Army of the Ohio |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War

|

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th President of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death on September 19, 1881,[1] a brief 200 days in office.

Garfield was born in Moreland Hills, Ohio and graduated from Williams College, Massachusetts in 1856. He married Lucretia Rudolph in 1858. In 1860, he was admitted to the Bar whilst serving as an Ohio State Senator (1859–1861). Garfield served as a major general in the United States Army during the American Civil War and fought at the Battle of Shiloh. He entered congress as a Republican in 1863, opposing slavery and secession. Following compromises with Ulysses S. Grant, James G. Blaine and John Sherman, Garfield became the Republican party nominee for the 1880 Presidential Election and successfully defeated Democrat Winfield Hancock.

Because he spent so little time as President, Garfield accomplished very little. In his inaugural address, Garfield outlined a desire for Civil Service Reform which was eventually passed by his successor Chester A. Arthur in 1883 as the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. His presidency was cut short after he was shot by Charles J. Guiteau while entering a railroad station in Washington D.C. on July 2, 1881. He was the second United States President to be assassinated. Following his death, Garfield was succeeded by Vice-President Chester A. Arthur.

Garfield was the only sitting member of the House of Representatives to have been elected President.[2]

Contents |

Early life

James Abram Garfield was born of Welsh ancestry on November 19, 1831 in a log cabin in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio.[3] His father, Abram Garfield, died in 1833,[4] when James Abram was 17 months old.[5] He was brought up and cared for by his mother, Eliza Ballou, sisters, and his uncle.[6]

In Orange Township, Garfield attended a predecessor of the Orange City Schools.[3] From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute[3] (later named Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio. He then transferred to Williams College[3] in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he was a brother of Delta Upsilon fraternity.[7] He graduated in 1856 as an outstanding student who enjoyed all subjects except chemistry.[8]

After preaching a short time at Franklin Circle Christian Church (1857–58),[3] Garfield ruled out preaching and considered a job as principal of a high school in Poestenkill, New York.[9] After losing that job to another applicant, he taught at the Eclectic Institute. Garfield was an instructor in classical languages for the 1856–1857 academic year, and was made principal of the Institute from 1857 to 1860.

On November 11, 1858, he married Lucretia Rudolph.[3] They had seven children (five sons and two daughters):[3] Eliza Arabella Garfield (1860–63); Harry Augustus Garfield (1863–1942); James Rudolph Garfield (1865–1950); Mary Garfield (1867–1947); Irvin M. Garfield (1870–1951); Abram Garfield (1872–1958); and Edward Garfield (1874–76). One son, James R. Garfield, followed him into politics and became Secretary of the Interior under President Theodore Roosevelt. In the mid-1860s, Garfield had an affair with Lucia Calhoun, which he later admitted to his wife,[3] who forgave him.[10]

Garfield decided that the academic life was not for him and studied law privately. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1860.[3] Even before admission to the bar, he entered politics. He was elected an Ohio state senator in 1859, serving until 1861.[5] He was a Republican all his political life.[3]

Military career

With the start of the Civil War, Garfield enlisted in the Union Army,[11] and was assigned to command the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry.[11] General Don Carlos Buell assigned Colonel Garfield the task of driving Confederate forces out of eastern Kentucky in November 1861, giving him the 18th Brigade for the campaign. In December, he departed Catlettsburg, Kentucky, with the 40th Ohio Infantry, the 42nd Ohio Infantry, the 14th Kentucky Infantry, and the 22nd Kentucky Infantry, as well as the 2nd (West) Virginia Cavalry and McLoughlin's Squadron of Cavalry. The march was uneventful until Union forces reached Paintsville, Kentucky, where Garfield's cavalry engaged the Confederate cavalry at Jenny's Creek on January 6, 1862. The Confederates, under Brig. Gen. Humphrey Marshall, withdrew to the forks of Middle Creek, two miles (3 km) from Prestonsburg, Kentucky, on the road to Virginia. Garfield attacked on January 9, 1862. At the end of the day's fighting, the Confederates withdrew from the field, but Garfield did not pursue them. He ordered a withdrawal to Prestonsburg so he could resupply his men. His victory brought him early recognition and a promotion to the rank of brigadier general on January 11.

Garfield served as a brigade commander under Buell at the Battle of Shiloh.[5] He then served under Thomas J. Wood in the subsequent Siege of Corinth. His health deteriorated and he was inactive until autumn, when he served on the commission investigating the conduct of Fitz John Porter. In the spring of 1863, Garfield returned to the field as Chief of Staff for William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland.

Later political career

In October 1862, while serving in the field, he was elected by the Republicans to the United States House of Representatives[12] for Ohio's 19th Congressional District in the 38th Congress.[5] As Congress did not meet until December 1863, Garfield continued to serve with the army and was promoted to major general after the Battle of Chickamauga. He resigned his commission, effective December 5, 1863, to take his seat in Congress. He was re-elected every two years, from 1864 through 1878, during the Civil War and the following Reconstruction era. He was one of the most hawkish Republicans in the House.

Garfield was one of three attorneys who argued for the petitioners in the famous Supreme Court case Ex parte Milligan (1866). The petitioners were pro-Confederate northern men who had been found guilty and sentenced to death by a military court for treasonous activities. The case turned on whether the defendants should, instead, have been tried by a civilian court. Garfield went on to plead other cases before the high court, but none was as high profile as his first argument before the Supreme Court in Milligan.

In 1872, he was one of many congressmen involved in the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal. Garfield denied the charges against him and it did not put too much of a strain on his political career since the actual impact of the scandal was difficult to determine. In 1876, when James G. Blaine moved from the House to the United States Senate, Garfield became the Republican floor leader of the House.

In 1876, Garfield was a Republican member of the Electoral Commission that awarded 20 hotly-contested electoral votes to Rutherford B. Hayes in his contest for the Presidency against Samuel J. Tilden. That year, he also purchased the property in Mentor that reporters later dubbed Lawnfield,[13] and from which he would conduct the first successful front porch campaign for the presidency. The home is now maintained by the National Park Service as the James A. Garfield National Historic Site.[13]

Election of 1880

In 1880, Garfield's life underwent tremendous change with the publication of the Morey letter, and the end of Democratic U.S. Senator Allen Granberry Thurman's term. In January the Ohio legislature, which had recently again come under Republican control, chose Garfield to fill Thurman's seat for the term beginning March 4, 1881.[14] However, at the Republican National Convention where Garfield supported Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman for the party's Presidential nomination, a long deadlock between the Grant and Blaine forces caused the delegates to look elsewhere for a compromise choice and on the 36th ballot Garfield was nominated. Virtually all of Blaine's and John Sherman's delegates broke ranks to vote for the dark horse nominee in the end. As it happened, the U.S. Senate seat to which Garfield had been chosen ultimately went to Sherman, whose Presidential candidacy Garfield had gone to the convention to support.

A central controversial issue during the Election of 1880 was Chinese immigration; an issue that could make or break any Presidential contender during this time period. Those in the West, particularly California, were against Chinese immigration claiming that growth in the Pacific would be limited. Easterners, such a Senator George F. Hoar, took a more philosophical and religious stand in favor of Chinese immigration. Garfield, on July 12, 1880 favored limiting Chinese immigration whom he labeled as "an invasion to be looked upon without solicitude." However, Garfield's primary supporter in the Senate, James G. Blaine, had sent out a letter that allegedly favored Chinese immigration. It was speculated that Blaine's letter cost Garfield valuable electoral votes in California.[15][16][17]

In the general election, Garfield defeated the Democratic candidate Winfield Scott Hancock, another distinguished former Union Army general, by 214 electoral votes to 155. (The popular vote had a plurality of less than 2,000 votes out of more than 8.89 million cast; see U.S. presidential election, 1880.) He became the only man ever to be elected to the Presidency straight from the House of Representatives and was, for a short period, a sitting representative, senator-elect, and president-elect. If sworn in, he would have been the first U.S. senator to be elected president; Warren G. Harding became the first to do so forty years later. However, Garfield resigned his other positions and, on March 4, 1881, took office as President, and never sat in the Senate, where that term began on the same day.

Presidency

President Garfield had only 4 months to establish his presidency before being fatally shot by Charles J. Guiteau, a deranged political office seeker, on July 2, 1881. During his limited time in office he was able to reestablish the independence of the presidency by defying the Republican Stalwart boss, Senator Roscoe Conkling. His inaugural address set the agenda for his presidency; however, he was unable to live long enough to implement these policies. Garfield's call for civil service reform, however, was fulfilled in the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act passed by Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur in 1883. Garfield's assassination was the primary motivation for the reform bill's passage.

Inaugural address

Snow covered much of the Capitol grounds during Garfield's inaugural address with a low turn out, about 7,000 people, who came to inauguration. Garfield was sworn into office by Chief Justice Morrison Waite on Friday, March 4, 1881.[18][19]

| “ | The elevation of the negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the Constitution of 1787.[18] | ” |

| “ | ...there was no middle ground for the negro race between slavery and equal citizenship. There can be no permanent disfranchised peasantry in the United States. Freedom can never yield its fullness of blessings so long as the law or its administration places the smallest obstacle in the pathway of any virtuous citizen.[18] | ” |

| “ | The nation itself is responsible for the extension of the suffrage, and is under special obligations to aid in removing the illiteracy which it has added to the voting population. For the North and South alike there is but one remedy. All the constitutional power of the nation and of the States and all the volunteer forces of the people should be surrendered to meet this danger by the savory influence of universal education.[18] | ” |

| “ | By the experience of commercial nations in all ages it has been found that gold and silver afford the only safe foundation for a monetary system. Confusion has recently been created by variations in the relative value of the two metals, but I confidently believe that arrangements can be made between the leading commercial nations which will secure the general use of both metals.[18] | ” |

| “ | The interests of agriculture deserve more attention from the Government than they have yet received. The farms of the United States afford homes and employment for more than one-half our people, and furnish much the largest part of all our exports. As the Government lights our coasts for the protection of mariners and the benefit of commerce, so it should give to the tillers of the soil the best lights of practical science and experience.[18] | ” |

| “ | The civil service can never be placed on a satisfactory basis until it is regulated by law. For the good of the service itself, for the protection of those who are intrusted with the appointing power against the waste of time and obstruction to the public business caused by the inordinate pressure for place, and for the protection of incumbents against intrigue and wrong...[18] | ” |

| “ | The Mormon Church not only offends the moral sense of manhood by sanctioning polygamy, but prevents the administration of justice through ordinary instrumentalities of law.[18] | ” |

Inaugural parade and ball

John Philip Sousa led the Marine Corps band both at the inaugural parade and ball. The ball was held in the National Museum, now the Arts and Industries Building, of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.[18]

Administration and Cabinet

Between his election and his inauguration, Garfield was occupied with constructing a cabinet that would balance all Republican factions. He rewarded Blaine by appointing him Secretary of State. He also nominated William Windom of Minnesota as Secretary of the Treasury, William H. Hunt of Louisiana as Secretary of the Navy, Robert Todd Lincoln as Secretary of War, Samuel J. Kirkwood of Iowa as Secretary of the Interior. He appointed Wayne MacVeagh of Pennsylvania Attorney General. New York was represented by Thomas Lemuel James as Postmaster General.

This last appointment infuriated Garfield's Stalwart rival Roscoe Conkling, who demanded nothing less for his faction and his state than the Treasury Department. The resulting squabble consumed the energies of the brief Garfield presidency. It overshadowed promising activities such as Blaine's efforts to build closer ties with Latin America, Postmaster General James's investigation of the "star route" postal frauds, and Windom's successful refinancing of the federal debt. The feud with Conkling reached a climax when the President, at Blaine's instigation, nominated Conkling's enemy, Judge William H. Robertson, to be collector of the port of New York. Conkling raised the time-honored principle of senatorial courtesy in attempting to defeat the nomination, but to no avail. Finally he and his junior colleague, Thomas C. Platt, resigned their Senate seats to seek vindication, but they found only further humiliation when the New York legislature elected others in their places. Garfield's victory was complete. He had routed his foes, weakened the principle of senatorial courtesy, and revitalized the presidential office.[20]

President Garfield's only official social function made outside the White House was a visit to the Columbia Institution for the Deaf (later Gallaudet University) in May 1881.[21]

| The Garfield Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | James A. Garfield | 1881 |

| Vice President | Chester A. Arthur | 1881 |

| Secretary of State | James G. Blaine | 1881 |

| Secretary of Treasury | William Windom | 1881 |

| Secretary of War | Robert Todd Lincoln | 1881 |

| Attorney General | Wayne MacVeagh | 1881 |

| Postmaster General | Thomas L. James | 1881 |

| Secretary of the Navy | William H. Hunt | 1881 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Samuel J. Kirkwood | 1881 |

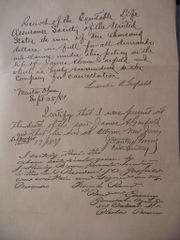

Only Executive Order

Garfield's one and only executive order was to give executive government workers the day off on May 30, 1881, in order to decorate the graves of those who died in the Civil War.[22]

-

- Executive Order

- May 28, 1881

- Dear Sir:

- I am directed by the President to inform you that the several Departments of the Government will be closed on Monday, the 30th instant, to enable the employees to participate in the decoration of the graves of the soldiers who fell during the rebellion.

- Very respectfully,

- J. Stanley Brown, Private Secretary.

- Addressed to the heads of the Executive Departments, etc.

Judicial appointments

Despite his short tenure in office, Garfield was able to appoint a Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States, and four other federal judges.

Supreme Court

| Judge | Seat | State | Began active service |

Ended active service |

| Stanley Matthews | seat 6 | Ohio | May 12, 1881 | March 22, 1889 |

Lower courts

| Judge | Court | Began active service |

Ended active service |

| Don Albert Pardee | Fifth Circuit |

May 13, 1881 | September 26, 1919[23] |

| Alexander Boarman | W.D. La. | May 18, 1881 | August 30, 1916 |

| Addison Brown | S.D.N.Y. | June 2, 1881[24] | August 30, 1901 |

| LeBaron B. Colt | D.R.I. | March 21, 1881 | July 23, 1884 |

Assassination

Garfield had little time to savor his triumph. He was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, disgruntled by failed efforts to secure a federal post, on July 2, 1881, at 9:30 a.m. The President had been walking through the Sixth Street Station of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad (a predecessor of the Pennsylvania Railroad) in Washington, D.C.. Garfield was on his way to his alma mater, Williams College, where he was scheduled to deliver a speech, accompanied by Secretary of State James G. Blaine, Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln (son of Abraham Lincoln[25]) and two of his sons, James and Harry. The station was located on the southwest corner of present day Sixth Street Northwest and Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C. (The West Building of the National Gallery of Art now occupies this site; the rotunda of that building sits astride the former location of Sixth Street directly south of Constitution Avenue.) As he was being arrested after the shooting, Guiteau repeatedly said, "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts! I did it and I want to be arrested! Arthur is President now!"[26] which briefly led to unfounded suspicions that Arthur or his supporters had put Guiteau up to the crime. (The Stalwarts strongly opposed Garfield's Half-Breeds; like many vice presidents, Arthur was chosen for political advantage, to placate his faction, rather than for skills or loyalty to his running-mate.) Guiteau was upset because of the rejection of his repeated attempts to be appointed as the United States consul in Paris – a position for which he had absolutely no qualifications. Garfield's assassination was instrumental to the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act on January 16, 1883.

One bullet grazed Garfield's arm; the second bullet lodged in his spine and could not be found, although scientists today think that the bullet was near his lung. Alexander Graham Bell devised a metal detector specifically to find the bullet, but the metal bed frame Garfield was lying on made the instrument malfunction. Because metal bed frames were relatively rare, the cause of the instrument's deviation was unknown at the time. Garfield became increasingly ill over a period of several weeks due to infection, which caused his heart to weaken. He remained bedridden in the White House with fevers and extreme pains. On September 6, the ailing President was moved to the Jersey Shore in the vain hope that the fresh air and quiet there might aid his recovery. In a matter of hours, local residents put down a special rail spur for Garfield's train; some of the ties are now part of the Garfield Tea House. The beach cottage Garfield was taken to has been demolished.

Garfield died of a massive heart attack or a ruptured splenic artery aneurysm, following blood poisoning and bronchial pneumonia, at 10:35 p.m. on Monday, September 19, 1881, in the Elberon section of Long Branch, New Jersey. The wounded President died exactly two months before his 50th birthday. During the eighty days between his shooting and death, his only official act was to sign an extradition paper.

Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss, (who was a Doctor of Medicine but whose given name was also "Doctor"[29][30][31]) Garfield's chief doctor, recorded the following:

| “ | Only a moment elapsed before Mrs. Garfield was present. She exclaimed, 'Oh! what is the matter?' I said, 'Mrs. Garfield, the President is dying.' Leaning over her husband and fervently kissing his brow, she exclaimed, 'Oh! Why am I made to suffer this cruel wrong?'...Restoratives, which were always at hand, were instantly resorted to. In almost every conceivable way it was sought to revive the rapidly yielding vital forces. A faint, fluttering pulsation of the heart, gradually fading to indistinctness, alone rewarded my examinations. At last, only moments after the first alarm, at 10:35, I raised my head from the breast of my dead friend and said to the sorrowful group, 'It is over.'

Noiselessly, one by one, we passed out, leaving the broken-hearted wife alone with her dead husband. Thus she remained for more than an hour, gazing upon the lifeless features, when Colonel Rockwell, fearing the effect upon her health, touched her arm and begged her to retire, which she did."[32] |

” |

Most historians and medical experts now believe that Garfield probably would have survived his wound had the doctors attending him been more capable.[33] Several inserted their unsterilized fingers into the wound to probe for the bullet, and one doctor punctured Garfield's liver in doing so. This alone would not have caused death as the liver is one of the few organs in the human body that can regenerate itself. However, this physician probably introduced Streptococcus bacteria into the President's body and that caused blood poisoning for which at that time there were no antibiotics.

Guiteau was found guilty of assassinating Garfield, despite his lawyers raising an insanity defense. He insisted that incompetent medical care had really killed the President. Although historians generally agree that poor medical care was an element, it was not a legal defense. Guiteau was sentenced to death, and was executed by hanging on June 30, 1882, in Washington, D.C.

Garfield was buried, with great solemnity, in a mausoleum in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio.[34] The monument is decorated with five terracotta bas relief panels by sculptor Caspar Buberl, depicting various stages in Garfield's life. Originally, he was interred in a temporary brick vault in the same cemetery. In 1887, the James A. Garfield Monument was dedicated in Washington, D.C. A cenotaph to him is located in Miners Union Cemetery in Bodie, California. On the grounds of the San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers stands a monument to the fallen president completed in 1884; it was designed by sculptor Frank Happersberger.

At the time of his death, Garfield was survived by his mother. He is one of only three presidents to have predeceased their mothers. The others were James K. Polk and John F. Kennedy.

On January 12, 2010, a previously unknown life insurance policy on the life of Garfield was discovered in Orient, New York. The policy was found in a family scrap book dating from the same period of his death and had a benefit amount of $10,000. It was opened on May 18, 1881, just 45 days prior to the date Garfield was shot by Guiteau, and was surrendered and signed by Lucretia Garfield and Joseph Stanley-Brown, both witnesses to Garfield's death.[35]

The U.S. has twice had three presidents in the same year. The first such year was 1841. Martin Van Buren ended his single term, William Henry Harrison was inaugurated and died a month later, then Vice President John Tyler stepped into the vacant office. The second occurrence was in 1881. Rutherford B. Hayes relinquished the office to James A. Garfield. Upon Garfield's death, Chester A. Arthur became president.

Legacy

James Garfield was featured on the series 1886 $20 Gold Certificate,[36] a currency note considered to be of moderate rarity and quite valuable to collectors.

Garfield Avenue in the suburb of Five Dock, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia is named after James A. Garfield, as is Garfield Street in Chelsea, Michigan, and the suburb of Brooklyn, Wellington, New Zealand.

Upon officially becoming a town, a Kansas settlement that went by the name Camp Riley renamed itself Garfield City to pay tribute to the politician, who once visited the settlement during military duty at the nearby Fort Larned. Garfield City is now known as Garfield, Kansas and had a population of under two hundred people at the 2000 census.

A sandstone statue of Garfield was dedicated in May 2009 on the campus of Hiram College. A week later, the statue was decapitated by vandals.[37] The missing head was recovered in July 2009.[38]

James A. Garfield School District is located in Garrettsville, Ohio, about 5 miles east of Hiram College, where Garfield studied, taught and later became president in 1857 at the age of 26. The district consists of 1,580 students in grades kindergarten through 12.

Individual distinctions

- Garfield was a minister and an elder for the Church of Christ (Christian Church), making him the only member of the clergy to date to serve as President.[39] He is also claimed as a member of the Disciples of Christ, as the different branches did not split until the 20th century. Garfield preached his first sermon in Poestenkill, New York.[40]

Garfield Monument at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio

Garfield Monument at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio - Garfield is the only person in U.S. history to be a Representative, Senator-elect, and President-elect at the same time. To date, he is the only Representative to be directly elected President of the United States.

- In 1876, Garfield discovered a novel proof[41] of the Pythagorean Theorem using a trapezoid while serving as a member of the House of Representatives.[42]

- Garfield was the first ambidextrous president. It was said that one could ask him a question in English and he could simultaneously write the answer in Latin with one hand, and Ancient Greek with the other, two languages he knew.[43]

- Garfield was a descendant of Mayflower passenger John Billington through his son Francis, another Mayflower passenger.[44] John Billington was convicted of murder at Plymouth Mass. 1630.[45]

- Garfield was related to Owen Tudor, and both were descendants of Rhys ap Tewdwr.[46]

- Garfield juggled Indian clubs to build his muscles.[47]

- Garfield was the first left-handed President.[48]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- List of assassinated American politicians

- List of United States Presidents who died in office

- List of United States presidents

- List of Presidents of the United States

- U.S. Presidents on U.S. postage stamps

References

- ↑ Frederic D. Schwarz "1881: President Garfield Shot," American Heritage, June/July 2006.

- ↑ [name=ohc170>http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=170]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 http://jamesgarfieldfacts.com/

- ↑ http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=170

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 164. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

- ↑ Conwell, Russell H.; John Davis Long (1881). The Life, Speeches, and Public Services of James A. Garfield. Boston: B.B. Russell. pp. 34, 53. http://books.google.com/?id=KmMPAAAAYAAJ&printsec=titlepage. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- ↑ Notable DUs. Delta Upsilon Fraternity. Politics and Government. URL retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ↑ James Garfield. American-Presidents.com. Accessed November 1, 2009.

- ↑ Peskin, Allan (1978). Garfield. Kent State University Press. pp. 45. ISBN 0873382102.

- ↑ "Garfield, James A.". Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to American Presidents. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. http://www.britannica.com/presidents/article-9036074. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 [3]

- ↑ State legislatures, not voters, chose U.S. senators until the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment.

- ↑ The Tariff review, Volumes 63-64. May 30, 1919. p. 344. http://books.google.com/?id=fHLnAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA344&dq=Garfield+desires+to+stop+Chinese+immigration&cd=1#v=onepage&q=Garfield%20desires%20to%20stop%20Chinese%20immigration. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ "Letter Accepting the Presidential Nomination". July 12, 1880. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=76221. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ From 1876 to 1882, it was assumed that every candidate for political office out of necessity had to state their individual position on Chinese immigration; either in favor or against the controversial issue.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 James A. Garfield

- ↑ Garfield's Inaugural Address Draft

- ↑ Garfield, James Abram. American National Biography, 2000, American Council of Learned Societies.

- ↑ Gallaudet, Edward Miner. History of the Columbia Institution for the Deaf.

- ↑ "The American Presidency Project". 1999-2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=69145. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ The old Fifth Circuit was abolished on June 16, 1891 in favor of the newly created United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, to which Pardee was assigned by operation of law, and on which he served until his death on September 26, 1919.

- ↑ Recess appointment; formally nominated on October 12, 1881, confirmed by the United States Senate on October 14, 1881, and received commission on October 14, 1881.

- ↑ Mr. Lincoln's White House: Robert Todd Lincoln, The Lincoln Institute, Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- ↑ Doyle, Burton T.; Swaney, Homer H (1881). Lives of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Washington: R.H. Darby. p. 61. ISBN 0104575468. http://www.archive.org/stream/livesofjamesa00doyle/livesofjamesa00doyle_djvu.txt.

- ↑ Cheney, Lynne Vincent. "Mrs. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper". American Heritage Magazine. October 1975. Volume 26, Issue 6. URL retrieved on January 24, 2007.

- ↑ "The attack on the President's life". Library of Congress. URL retrieved on January 24, 2007.

- ↑ Rutkow, Ira (2006), James A. Garfield, New York, New York: Macmillan Press, p. 85, ISBN 9780805069501, OCLC 255885600, http://books.google.com/?id=fDJp7exj2R0C&lpg=PP1&pg=PA126

- ↑ Baxter, Albert (1891), History of the city of Grand Rapids, Michigan, New York, New York: W.W. Munsell & Co., p. 699, OCLC 6359377, http://books.google.com/books?id=l2SbZhZfYfEC&pg=PA699

- ↑ Lamb, Daniel Smith, ed. (1909), History of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia: 1817-1909, Washington, D.C.: Medical Society of the District of Columbia, p. 277, OCLC 7580275, http://books.google.com/books?id=ci-gAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA277

- ↑ [4]|The Death Of President Garfield, 1881|Bliss, D. W., The Story Of President Garfield's Illness, Century Magazine (1881); Marx, Rudolph, The Health of the Presidents (1960); Taylor, John M., Garfield of Ohio (1970).

- ↑ A President Felled by an Assassin and 1880’s Medical Care New York Times, July 25, 2006.

- ↑ Vigil, Vicki Blum (2007). Cemeteries of Northeast Ohio: Stones, Symbols & Stories. Cleveland, OH: Gray & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59851-025-6

- ↑ [5]

- ↑ Orzano, Michele. "Learning the language". Coin World. November 2, 2004. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- ↑ Associated Press (May 18, 2009). "Statue of Former President Loses Head in Ohio". cbsnews.com. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2009/05/18/ap/strange/main5021686.shtml. Retrieved August 26, 2009. "Someone has beheaded a statue of President James Garfield that was installed last week at an Ohio college."

- ↑ Brown, Shawn (July 31, 2009). "Hiram College and Village of Hiram officials announce the return of head of Garfield statue". news.hiram.edu (Hiram College Office of College Relations). http://news.hiram.edu/?p=4096. Retrieved August 26, 2009. "Hiram College and Village of Hiram officials today announced that the head of the statue of James A. Garfield which was stolen on Thursday, May 14, has been returned."

- ↑ James A. Garfield Mr. President. Profiles of Our Nation's Leaders. Smithsonian Education. URL retrieved on May 11, 2007.

- ↑ Sullivan, James (1927). "Chapter VI. Rensselaer County". The History of New York State, Book III. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. http://www.usgennet.org/usa/ny/state/his/bk3/ch6.html. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ↑ [6]

- ↑ "Pythagoras and President Garfield", PBS Teacher Source, URL retrieved on February 1, 2007.

- ↑ American Presidents: Life Portraits, C-SPAN, Retrieved November 29, 2006

- ↑ "Famous Descendants of Mayflower Passengers". Mayflower History. URL retrieved March 31, 2007.

- ↑ Borowitz, Alfred. "The Mayflower Murderer". The University of Texas at Austin. Tarlton Law Library. URL retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ Genealogy Report: Ancestors of Pres. James Abram Garfield

- ↑ Paletta, Lu Ann; Worth, Fred L (1988). The World Almanac of Presidential Facts. World Almanac Books. ISBN 0345348885.

- ↑ Tenzer Feldman, Ruth (2005). James A. Garfield. Lerner Publications. ISBN 0822513986.

Further reading

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield, Avalon Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-7867-1396-8

- Freemon, Frank R., 2001: Gangrene and glory: medical care during the American Civil War; Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07010-0

- Peskin, Allan "James A. Garfield: Supreme Court Counsel" in Gross, Norman, ed., America's Lawyer-Presidents: From Law Office to Oval Office, Chicago: Northwestern University Press and the American Bar Association Museum of Law, 2004, pp. 164–173. ISBN 0-8101-1218-3

- King, Lester Snow: 1991 Transformations in American Medicine : from Benjamin Rush to William Osler / Lester S. King. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, c1991. ISBN 0-8018-4057-0

- Peskin, Allan Garfield: A Biography, The Kent State University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-87338-210-2

- Vowell, Sarah "Assassination Vacation", Simon & Schuster, 2005 ISBN 0-7432-6004-X

External links

- James Garfield: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Garfield, Harding, and Arthur

- Official whitehouse.gov biography

- Inaugural Address

- Encarta (Archived October 31, 2009)

- An image of Garfield's Civil War Pension File from the National Archives

- Raw Deal

- Biography from John T. Brown's Churches of Christ (1904)

- James A Garfield National Historic Site

- James A. Garfield Birthplace

- James A. Garfield at Findagrave

- Garfield Monument

- James A. Garfield at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress Retrieved on February 12, 2008

- Extensive essay on James Garfield and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Rutherford B. Hayes |

President of the United States March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 |

Succeeded by Chester A. Arthur |

| United States House of Representatives | ||

| Preceded by Albert G. Riddle |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 19th congressional district March 4, 1863 – March 4, 1881 |

Succeeded by Ezra B. Taylor |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Rutherford B. Hayes |

Republican Party presidential candidate 1880 |

Succeeded by James G. Blaine |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by Henry Wilson |

Persons who have lain in state or honor in the United States Capitol rotunda September 21, 1881 – September 23, 1881 |

Succeeded by John A. Logan |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||